PRC Positive Messaging Frames Successful Colonization in Xinjiang

by Niva Yau

Executive Summary:

Through television broadcasts overseas, like Jongugu Sapar in Kyrgyzstan, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) presents an image of ethnic harmony and economic development in Xinjiang, downplaying or omitting signs of colonialism, forced labor, or suppression of Turkic cultural identity.

The PRC’s positive messaging about Xinjiang has been successful in Central Asia, where positive historical narratives about and some nostalgia for the Soviet Union influence perceptions of PRC actions.

By tailoring content to resonate with local beliefs, the PRC successfully projects its foreign policy goals and strengthens its regional influence. For instance, anti-colonial rhetoric, while rife in PRC discourse in Africa, goes unmentioned in Central Asia.

I have lost count of how many times foreign experts have asked me if Central Asians care about the abuses happening in Xinjiang. The Turkic territory, now part of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), is known locally as East Turkestan. Once part of Central Asia, the language of its people shares the same heritage as those of the wider region, and its food, culture, and religion are similarly inseparable.

What divides Xinjiang from Central Asia is not just the mountainous border but a colonization project that has continued, and in some cases accelerated, even as the rest of the region has begun to move in the opposite direction, decolonizing 30 years after independence from the Soviet Union. This background makes a huge difference. Transitional Central Asian states have not popularized, or even formed, a consensus over the many tragedies from the period of Soviet colonization. Despite an awareness of the PRC’s abuses on the other side of the border, these states have not made sense of them as colonial policies. Instead, they have been susceptible to the PRC’s positive messaging programs and shaping of the region’s information environment (Jamestown Perspectives, September 4).

'Jongugu Sapar' Blends Soviet Nostalgia to Tout Ethnic Harmony

Jongugu Sapar (Джунгого сапар/“Travel to China”), a successful daily PRC propaganda show in the Kyrgyz Republic, is a good example of the PRC’s positive messaging. The show has broadcast the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) economic and social activities in Xinjiang since the early 2000s. A nationally representative opinion survey completed by the Central Asia Barometer in the summer of 2022 found that 576 out of 1000 respondents reported knowledge of the show. Of those, nearly all had previously watched the show, and 70 percent found the content “favorable (нравится).” [1] In my informal conversations with Chinese-speaking Kyrgyz students, I was surprised to find that many had first learned about the PRC from the show and not from school textbooks.

We installed a small TV in our Bishkek office and watched the show each day for several months as part of a team activity. The presenter, an ethnic Kyrgyz woman from Xinjiang, speaks a Kyrgyz dialect mixed with a smattering of Mandarin Chinese words. My local colleagues sometimes found her diction incomprehensible. Still, they found her monotone delivery, stiff movements, and narrow range of facial expressions, as well as the overall presentation of the show, very nostalgic and reminiscent of Soviet-era broadcasts.

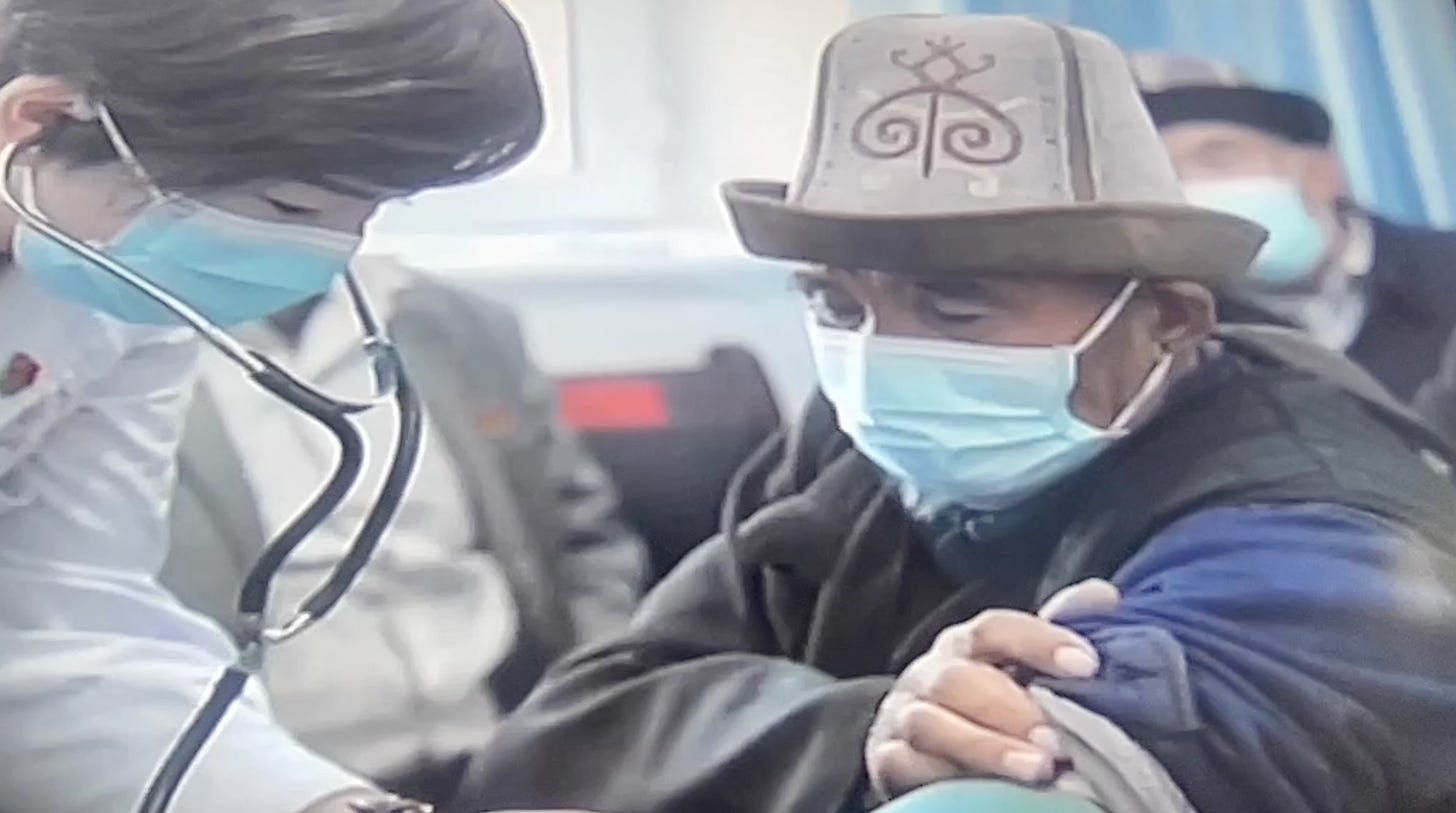

Figure 1: Screenshots from ‘Travel to China’

The show centers on themes of ethnic harmony, yet it depicts a clear divide between the Turkic population and the Han Chinese. Stories focused on Zhang Qian (張騫) and Ban Chao (班超), two Han Chinese diplomats celebrated for their significant contribution to Xinjiang, is the narrative the CCP uses to assert legitimate Han Chinese rule over the region. Not once were Turkic peoples’ cultural and historical heroes mentioned. Similarly, we never saw Turkic people speaking their native language to one another. All conversations began in Mandarin, only to be dubbed into Kyrgyz seconds later. Sinicized names of villages and towns were used repeatedly. No Islamic names were depicted at any point. Instead, the show highlighted archaeological findings suggesting a Buddhist presence and framed excavated artifacts as representations of Han Chinese life.

The Turkic population interviewed in the show were consistently portrayed in low-skilled roles such as farmers and seamstresses. Han Chinese, meanwhile, appeared as business owners, managers, lead engineers, or industrial specialists. Every archaeologist interviewed was Han Chinese. Only in select fields, like wildlife and forest conservation, traditional medicine, artisanal crafts, and ethnic cuisine, were members of the Turkic population shown in senior positions. This stark lack of elite Turkic representation reinforced an impression of Han superiority over the Turkic population.

Viewers See 'Resettlement Labor Programs' as Positive Economic Development

A striking departure from this subtle messaging were the stories about resettlement labor programs. The show featured unemployed women and those in rural areas who had enrolled in short-term vocational schools to learn skills such as sewing and gardening, eventually “graduating into employment” at factories and greenhouses in newly established settlements. In these settlements, an acute power dynamic was on display between the Han Chinese and the Turkic population. Senior roles such as teachers, library managers, metro administrators, hospital directors, and heads of elderly homes were all occupied by Han Chinese. One scene in particular left us uneasy: a group of Turkic women in striped pajamas, seated in a small room of bunkbeds, expressed gratitude to Han Chinese doctors for taking good care of them.

Figure 2: Screenshots from ‘Travel to China’

The resettlement labor programs described on the show bore an uncomfortable resemblance to the findings of Tomoya Obokata, the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, who concluded in a July 2022 report that forced labor among ethnic populations in Xinjiang has been occurring in sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing (UNHRC, July 19, 2022; see China Brief¸ February 14).

Viewers in the Kyrgyz Republic did not interpret what they saw this way. In follow-up in-depth interviews conducted between August 2022 and February 2023, we asked selected survey respondents who had seen the program for their thoughts on the show. Many framed what they saw positively, connecting it to their memories of the Soviet Union—a collectivist society they believed had been successful. A 66-year-old male government worker told us that the “hardworking people” depicted reminded him of those who “worked tirelessly” during the Soviet era. “We used to work like that,” he continued. “We were brought up to be hardworking. China encourages people to work hard … that’s why China is economically developing.”

The inability to perceive the CCP’s actions in Xinjiang as colonialism is closely tied to a similar lack of recognition of the Soviet Union as a colonial power. This shared historical perspective is a key factor behind the success of the PRC’s positive messaging about Xinjiang in the Kyrgyz Republic and across the region. The show not only reinforces an appealing image of Xinjiang but also strengthens local consensus around the success of China’s economy.

This sentiment echoed even among those who did not grow up under the Soviet Union, however. Some of these people believed that the collectivist regime had been a success. A 23-year-old female government worker told us, “Through this program, I learned that people in China are very hardworking.” She added that it seemed to her that the program was showing “the life of Kyrgyz people in the old days, perhaps under the USSR,” particularly in the people’s style of speech and the program’s overall content.

Figure 3: Screenshots from ‘Travel to China’

Conclusion

As long as the region remains in a transitional phase and is unable to decolonize fully, these sentiments are likely to be passed on to the next generation, who will continue to consume the PRC’s positive messaging. The irony is that the rhetoric of decolonization has long been part and parcel of the PRC’s overseas messaging. In Africa, for example, the PRC has deployed anti-colonial rhetoric for decades. In Central Asia, however, it remains silent on the issue. This suggests a normative hollowness and deep pragmatism to the PRC’s political communications. In each country, it aligns its positive messaging with specific foreign policy objectives, tailoring its content to resonate with the local population and regional context.

This piece originally appeared in Jamestown Perspectives. Check it out here!

Niva Yau is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. Her research work focuses on China-Central Asia relations and China’s new overseas security management infrastructure and initiatives. Between 2018 and 2023, Ms. Yau was based at the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Academy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, where she worked on commissioned research covering China’s foreign policy, trade, and security in its western neighborhood, covering Central Asia and Afghanistan. She is originally from Hong Kong and is currently based in Tokyo, Japan.

Notes

[1] The author privately commissioned this unpublished survey.