Chinese Roads in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan Bring Benefits to Beijing

Nargiza Muratalieva and Khursand Khurramov

Executive Summary:

China, through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), plays a central role in developing transit networks in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, aiming to unify regional road infrastructure and facilitate Chinese exports.

Chinese involvement provides economic benefits to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan but also gives China significant influence and increases the presence of its soft power in the region. Chinese companies dominate construction projects, often using Chinese funding, labor, and materials.

While these infrastructure projects help Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan build critical roadways, they also create dependency on China. Additionally, cost overruns, delays, and loan obligations often benefit Chinese interests more than local economies.

Kyrgyzstan and China opened a new border checkpoint, “Bedel,” on September 4, which required the construction of a road through the border of Kyrgyzstan’s Issyk-Kul Region and China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Akylbek Zhaparov, the chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of Kyrgyzstan, emphasized how this checkpoint and the construction of the adjoining Barskoon-Uchturpan-Aksu highway “will become not only the gateway for further economic cooperation, but also a bridge of friendship and mutual respect between our countries” (Cabinet of Ministers of Kyrgyzstan, September 4). In more ways than one, China is central to the development of Kyrgyzstan’s and Tajikistan’s growing transport networks, and unifying their respective road systems remains a strategic goal for both countries (Tajikistan’s Foreign Affairs Ministry, July 6, 2018). Achieving this goal, however, would be impossible for either without external assistance, which both rank in the top fifty of the world’s poorest countries. China’s financial heft and engineering capabilities create opportunities to make this goal a reality. Dushanbe and Bishkek see the local implementation of China’s global infrastructure program, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as an opportunity to overcome bottlenecks in their transport sectors. In contrast, Beijing sees the BRI as a chance to increase its exports to the Central Asian market.

Both sides’ expectations are being fulfilled, but Beijing may be gaining more from the relationship. China’s activities in Kyrgyzstan’s and Tajikistan’s transport sectors primarily benefit Chinese companies and provide Beijing with economic leverage while simultaneously providing soft power gains. According to Tajikistan’s transport minister, the country has built 2,407 kilometers (1,495 miles) of roads since independence in 1991 (Asia-Plus Tajikistan, May 31). In the same period, Kyrgyzstan has built 2,680 kilometers (1,665 miles) of roads. China has been a significant player in this, acting as a major contractor and financier by providing loans and grants (Radio Azatlyk, January 26).

Tajikistan’s Ministry of Transport claims that China has been the largest national contributor to the country’s expanding transport infrastructure, accounting for 26 percent of the total value, or $570.2 million (Asia-Plus Tajikistan, August 20). Of this sum, $37 million has come in grants, while the remaining $533.2 million were loans. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has provided 35 percent of the funding for Tajikistan’s roads, totaling $766.6 million. The largest single financier of Kyrgyzstan road infrastructure is the Export–-Import Bank of China (Chexim). According to Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Transport, the country has invested approximately $1.35 billion in road projects, with Chexim funding $390 million of this figure and the Asian Development Bank following with $267 million (Akchabar.kg, February 16, 2023).

Participation in constructing and modernizing Kyrgyzstan’s road system allows Beijing to monitor multimodal transport route development in the country. It boosts trade relations between the two countries, and gives preference to corridors connecting Kyrgyzstan with China. Kyrgyzstan imports Chinese products mainly by road-based transport. In the first half of 2024, trade turnover between Kyrgyzstan and China increased by 40.77 percent, amounting to $3.17 billion (24.kg, August 16). Most of this sum consists of Chinese exports: of the total figure, $3.12 billion were exports from China, while just $48 million were Kyrgyz exports. Most of the latter number were raw materials such as metal ores and oil. In 2023, this figure was nearly identical, with exports of Kyrgyz products to China composing only around 1.5 percent of the total exports between the two states (Kyrgyz National Statistical Committee, accessed October 30).

In Tajikistan, improved roads have led to increased trade, mostly in exports from China. In 2023, trade turnover between the countries was $1.5 billion, up 24.2 percent from 2022. $1.2 billion of this sum consisted of Chinese exports, while just $313.8 million were exports from Tajikistan. Here again, Tajikistan’s exports to China are primarily minerals and other raw materials. Interestingly, while China’s exports to Tajikistan increased by 42.8 percent between 2022 and 2023, Tajikistan’s exports to China decreased by 24.2 percent over the same period (Asia-Plus Tajikistan, February 3, 2023).

Reconstructing roads in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan also allows Chinese companies to earn money and employ Chinese citizens. Unlike funding from international institutions such as the Asian Development Bank, funding from China is generally provided on the condition that the project is built by a Chinese company. This tends to be equally true for all Chinese-funded ground transport projects in the two countries, be they road or rail. Chinese subcontractors earn a profit for Beijing. These organizations often utilize financing from Chinese banks and import their own equipment and construction materials, which are often exempt from tax and customs duties. Such conditions, for example, were imposed by Beijing when it provided a grant for constructing the Kal’ai Humb-Wanj road in Tajikistan (Radio Ozodi, June 17, 2021). Information regarding contracts financed by Chinese institutions is rarely made available, but a useful example might include the reconstruction of the Dushanbe-Dangara and Dushanbe-Chanak roads. The terms of this loan were 20 years at 2 percent interest, with a grace period of five years (Avesta.tj, August 25, 2009; Radio Ozodi, February 16, 2020). In both cases, the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) was chosen as the general contractor.

China’s leading role in constructing roads in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan is not only due to that country’s financing of such projects but also because Chinese companies are increasingly winning many of the tenders that are financed from Dushanbe’s and Bishkek’s state budgets or other international financial institutions. According to the Asian Development Bank, from 2017 to 2021, Chinese companies won tenders worth about $154.3 million in Tajikistan and about $106.8 million in Kyrgyzstan (Asian Development Bank, accessed October 30).

In 2019, CRBC built 728 kilometers (452 miles) of roads in Tajikistan for a total of $779 million. This is due in no small part to the low prices offered by Chinese companies, such as CRBC, to complete such projects (Eurasianet, July 26, 2022). Nurali—an engineer from Dushanbe who has supervised various road projects in Tajikistan—stated that when “Chinese companies [come] in … no one can compete with them.” Nurali claims that the Chinese state supports their bids:

These companies can reduce their cost by 20–25 percent … The amount they do not get is compensated to them by the [Chinese] state if they win the tender. That money still goes to China, the companies are doing business, providing employment for their people, paying taxes, and the state is interested in that (Author’s interview, August 10–17).

The benefits of many Chinese-financed road projects built as part of the BRI are still uncertain. Some of these projects have become long-term construction projects, largely due to the missing of deadlines. For example, CRBC began construction of the North-South Road project in 2015, but it is still not completed. The road is expected to open at the end of 2024, but it has overrun its initial cost by $887 million (Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting, June 5, 2020; Akchabar.kg, March 8, 2023). This is made more glaring by recent revelations that Chinese contractors had overstated the cost of the work in their original bid by at least 30 percent. Now that the road is almost complete, Kyrgyz officials will have to find funds to manage it, pay off the loans acquired, and make the transportation route profitable.

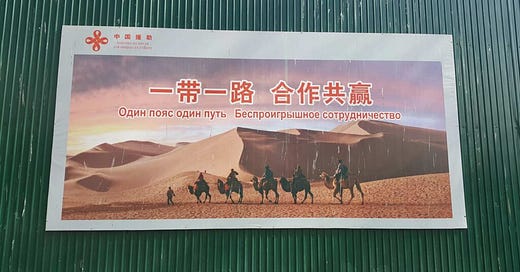

The ubiquity of Chinese companies in constructing Tajikistan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s roads has yielded soft power gains for Beijing. In Kyrgyzstan, especially in the capital of Bishkek, China provides grants for the construction of interchanges to solve traffic jams (Cin’khyla Novosti, February 20, 2022). After work is completed, Chinese companies often leave a reminder of the role Beijing plays for citizens by placing wide banners across the road promoting the BRI (Thepeoplesmap.net, January 12, 2022).

Whether or not China finances roads and infrastructure projects, the significant presence of Chinese companies creates an inflated sense of China’s largesse in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. All of the individuals interviewed by these authors along the Chinese-built road in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan region believed that all roads in Tajikistan are built at the expense of China because Chinese companies mainly carry out their construction. For Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, China acts as the top trade partner, an important investor, and the main hope for breaking their landlocked isolation. Both countries receive new roads out of the exchange, but China has benefited the most from cooperation through its influence over Tajikistan’s and Kyrgyzstan’s citizens.

This article was originally published in Eurasia Daily Monitor.

Nargiza Muratalieva holds a PhD in political science and is a part-time associate professor in the International and Comparative Politics Department at the American University of Central Asia (AUCA). She is a contributor to the Spheres of Influence Uncovered project and participant of other research projects on Central Asia. Ms. Muratalieva has extensive experience working in regional think tanks and nongovernmental organizations. Her research is focused on Central Asia’s international relations and its regional cooperation.

Khursand Khurramov is a journalist specializing in the domestic and foreign policies of Tajikistan, particularly in its relations with China, issues of authoritarianism, and human rights violations. He collaborates with international independent media and think tanks, providing in-depth analysis and insights on these pressing topics.